Folktales Predate Methuselah

I can’t pinpoint when, but I’ve long been interested in folktales, fables, and fairy tales. To say children everywhere heard oral tales recited or their written versions read to them may be a stretch. Yet, folktales exist in Western and Eastern cultures. They are free spirits, ever-growing, and changing in time and space. They are older than Methuselah.

Why do I enjoy them? Folktales come from the soul of common people, are told by them, handed down like heirlooms from parents to their children, and passed on from generation to generation. And folktales cross geographical boundaries freely without prejudice or malice. They are entertaining, often with a moral bent. And yet they also let “the folk” vent their dislikes of corrupt higher-ups in the voices of animal characters.

Folktales Go Wherever Folks Live

Folktales surround continents like oceans—from India to countries in the Middle East, to countries in Western Europe, to the United Kingdom, and across the Atlantic to the Americas. They intermingle and dress accordingly. They change not only settings and their place of origin but also from the past to the present while retaining their simple narrative. And more than anything else, their fluidity and adaptability separate them from fables, fairy tales, and myths.

One folktale character entered my life at an early age. His name is Giufà, which in the old Sicilian language means village fool. Here’s a tale of that folk character.

“Giufà, Pull the Door!”

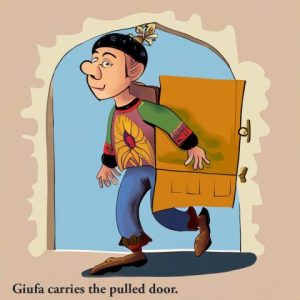

One day, before Giufà’s mother went to church, she told her son, “Giufà, I’m going to mass. Take care, and after I close the door, make sure you pull it.” As soon she left, Giufà went to the door and began to pull it. He pulled and pulled so hard that it came off the hinges. He carried the door on his back and went to the church to bring it to his mother. “Here’s the door you told me to pull.”

Discovering Giufà

I share a dual heritage—German and Sicilian. My mother’s parents immigrated from Sicily at the turn of the nineteenth century. And like most immigrants, they brought more than their personal belongings in their luggage. They brought their culture and their way of life.

My mother had two sisters who were born in Sicily. So it’s from my Aunt Josephine (Giuseppina); I first heard about Giufà. And as I said, it means village fool. But in usage, it portrays a childish, gullible, or clownish guy.

Giufà popped into my Aunt’s conversations when she referred to someone who acted foolishly, usually a younger brother or neighbor. And she called me Giufà once or twice because, as a curious five-year-old, I opened a can of lard and smeared it in my hair and face before anyone noticed.

On another occasion, I climbed a ladder my grandfather left against his storage shed. I stomped around on its flimsy metal roof, almost giving my grandmother a heart attack when she saw me.

Giufà Arrives in Sicily

Folktales have a history of transforming themselves in several ways. They travel with the teller of the tale, and they sometimes change. The character of Giufà has origins in Turkey (formerly Anatolia).

“the origins of Giufa are not entirely Sicilian… the inspiration for this character derives from… Nasreddin Khoja, a man who probably existed at the beginning of the eleventh century in Anatolia (now Turkey). He was a well-known teacher in the Arab world, whose name changed from Hoca to Khoja, from Khoja to Djuha, and from Djuha to Jusuf, from which the current Giufà.”

How did that come about? The Saracens (Arab Muslims or Moors) ruled Sicily from 831 until 1061, a period of two hundred and fifty years. The first Arab settlement in Sicily occurred at Mazara in 827.

On March 26, 2011, a story entitled “Giufa’s Judgement” appeared in the San Angelo News. Here’s the first paragraph. To read the full folktale, click on the link. Under photo credits, I see the word “adapted.” So I wonder how much this narrative departs from the original folktale.

“Once upon a time a mother sent her son, the young fool whose name was Giufa, out into the woods to gather herbs. Giufa set off full of spirit, and all day long he picked rosemary and basil and thyme. He worked so long, filling his bag to the brim, that by the time he was heading for home, the sun had set.”

What I find so intriguing about folktales is their longevity and adaptability. They predate manuscripts and books. They’ve survived centuries, and they remain popular. And when I consider the novels, plays, and movies folktales have inspired, it’s almost like reading a tale within a folktale.

Fun to read. I have read the history of Sicily, very interesting.

Nice story! I liked the personal elements that you brought in!

Nice story! I especially liked the personal elements you brought in to the story!

I’m glad you liked it. I have several books on Italian and Sicilian Folktales.

Chris, thanks for the feedback on the personal elements I included in the story. I pondered whether readers would enjoy them.